Introducing the first edition of ‘Toska’, a newsletter by a nobody (with a lot to say!) I look back on my history and the circumstances of my adoption.

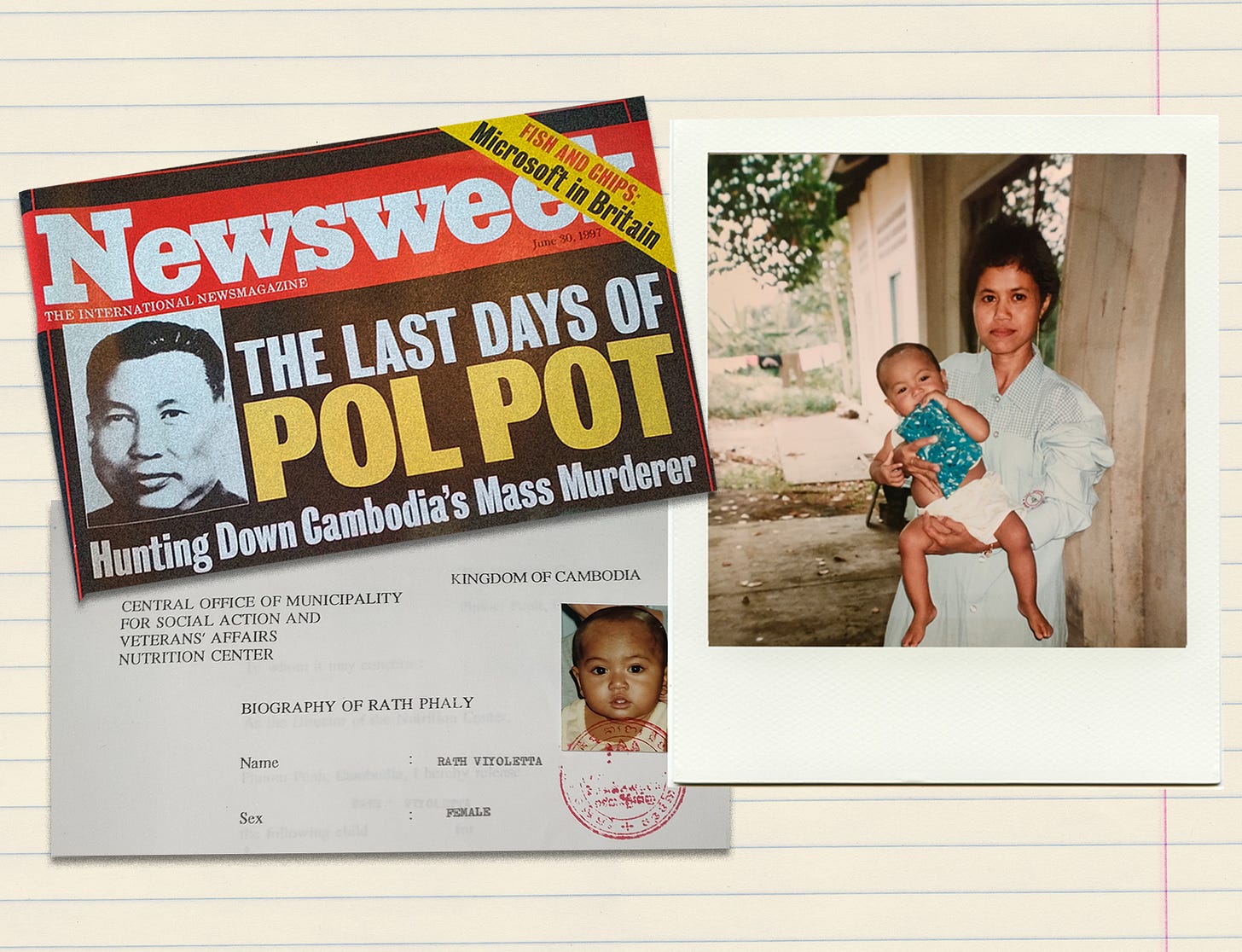

On the 4th March 1997, a baby girl in Cambodia was abandoned at Phnom Penh’s main state-run orphanage, the Nutrition Center. Her name was unknown. So, she was called Viyoletta Rath, with ‘Rath’ denoting she was a ward of the government.

At over a year old, her stomach was distended like that of Buddha, which a doctor would later attribute to malnutrition. At the orphanage, she was fed a mixture of rice porridge, alongside sugar water and tea. But she was otherwise healthy.

The Nutrition Center, and its director Yuon Sovanna, were in the eye of the storm of accusations of child trafficking. Such was the international outcry over intercountry adoptions from Cambodia, which first started in 1989, a moratorium was placed in 1991 after a series of ‘controversial adoptions’. Some newspapers likened the practice to baby-selling. The moratorium was lifted in 1994. Serious questions remained over how children came to be adopted.

Against this backdrop of controversy, Viyoletta was adopted by a British couple.

In 2003, Sovanna told the Sydney Morning Herald: "It is better than the children living here. At least they have the chance of a decent life.” In June 1996, the Phnom Penh Post reported that most intercountry adoptions were through the Nutrition Center, alongside another orphanage, Cambodia House.

One particular name became associated with dubious adoptions: Lauryn Galindo.

***

In 2008, Cambodia was placed on a restricted list of countries which suspended adoptions from abroad by UK residents.

The reasoning was just: concerns over the prevalence of child trafficking and evidence of “systemic falsification of Cambodian official documents related to the adoption of children” meant that it “would be contrary to public policy to further the bringing of children into the United Kingdom from Cambodia”.

Four years earlier, Lauryn Galindo, a US woman, was sentenced to 18 months in prison for facilitating intercountry adoptions of around 700 children from Cambodia, mainly to the US, from 1997 to 2001. She has always maintained it was the responsibility of the Cambodian government and orphanages to ensure children were legally abandoned.

But in some instances, the children had living parents who had been coerced into giving them up, been paid, or had placed their children into orphanages due to poverty with the expectation they would be able to bring them home later.

Galindo’s name was attached to the Nutrition Center, along with Sea Visoth, an alleged Cambodian ‘middleman’ and her former driver. In 2004, Galindo pleaded guilty in federal court to conspiracy to commit visa fraud and to launder money. She made roughly $8 million in profits from facilitating these adoptions.

The shadow of Galindo’s association with the Nutrition Center is an uneasy one. When trying to ascertain the circumstances of my abandonment with Nutrition Center staff in 1997, my mother tells me that one day my birth father, a man called Sambath Dy, turned up to the orphanage with my maternal aunt.

The encounter was unexpected and hampered by language barriers. Sambath spoke Khmer — which was then translated into French by the center's staff to my mother — whose own French was rudimentary but enough navigate the adoption process.

Viyoletta Rath was born Thierry Dy.

Viyoletta Rath became Dani Cole.

There is a photo of them together — my mother, maternal aunt, birth father — smiling. The photograph was confusing when saw it for the first time. I feel angry, I wrote in my diary. Shouldn't they be sad?

“He never asked for money,” Mum told me over the phone recently. “He was happy for you. He was grateful he could give you the opportunity for a better life.” She has assured me repeatedly I was not one of Galindo’s ‘babies’.

I like to think I was loved — that I was loved so much, my Khmer father thought it was kinder to give me away. My birth mother, Srey Yoeurn, was dead. He had four other children. This fifth child was too much. I cannot blame him for his decision.

According to documents, my birth parents were born in 1950s. They would have been in their twenties when the Khmer Rouge seized power. Between 1975 to 1979, under the leadership of dictator Pol Pot (also known as Saloth Sar), the Khmer Rouge killed an estimated 2 to 3 million people through starvation, forced labour, and execution.

As I approach the age that Mum found me, my thoughts keep turning to Cambodia.

I want to know if the Khmer family ever thought about me. I want to know how my birth parents lived through the atrocities of genocide.

And I want to know, truly know, if I was loved by them.

This article was adapted from www.dani-cole.co.uk